News: Emmerdale’s Cain Dingle Faces Heart-Wrenching Cliffhanger Leaving Fans Devastated!

Cain’s Breaking Point — A Shocking Return, Family Fury and a Cliffhanger That Leaves the Village Holding Its Breath

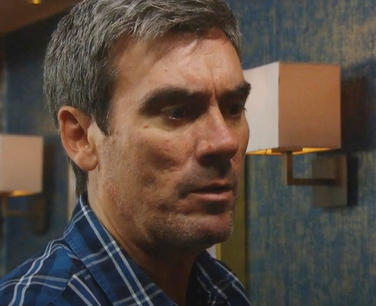

They say grief changes a man. For Cain Dingle, grief has been an ugly, corrosive companion — one that’s forced him out of himself and into dark, reckless choices. He returns to the village not as the cocky, stalwart Dingle the community remembers, but as a man frayed at the edges, dragging with him the weight of failure, loss and a recklessness that threatens everyone around him.

His arrival is heavy with history. Cain’s ill-advised mission to France — a desperate attempt to find John Sugden and avenge Nate — ended in humiliation: arrested, beaten down, and ultimately empty-handed. He confesses to Moira, blunt and bitter: “It was all a waste of time.” That culpable resignation hangs in the air. He met an army pal of John’s who’d long since lost contact; he had chances to finish things when they mattered and didn’t take them. The admission is a crack in the Dingle armour, and the family senses it immediately.

What follows is a descent: heavy drinking, self-destructive episodes and a string of choices that push Cain further away from his role as the family’s reluctant anchor. Moira, ever the voice of steadiness, tries to pull him back, reminding him of his responsibilities — in particular, of the anniversary of his father Zach’s death. Cain promises to pay his respects with Belle and Sam, but something in him snaps; he loses patience, he snaps at Moira, and then he heads out, only to be found later drinking alone in the garage. When good men reach for him, the old Cain responds with a brittle, hurt edge — a man convinced that justice for Nate will never arrive while Jon remains on the run.

The family fractures in the aftermath. At the Woolpack, Moira watches Belle and Sam lean on each other at the memory of their father; Cain’s absence at the grave is noticed, and disappointment settles like a mirror. Belle, distraught, shares a heart-to-heart with Zach’s memorial, promising to protect their kin even if Cain won’t help himself. At home, the knives come out. Cain’s temper snaps at his son Kyle — a tender, painful exchange where a “man of the match” award is knocked over and broken in Cain’s rage. Kyle’s frustration is simple and piercing: his father missed his game, had promised to be there, and was not. That broken trophy becomes a symbol of Cain’s unraveling: promises shattered, family rituals abandoned, and a man losing his grip.

Others try to intervene. Liam finds Cain drinking in the garage and a GP attempts to reason with him about the trauma of losing a child. But Cain’s responses are jagged; he brushes aside condolence, fixates on the injustice that Nate’s killer is still free, and rages at the impotence of the law while nursing his own private failures. The show lets these moments breathe — there is no melodrama, only small, human detonations that compound until the whole household trembles.

The emotional pressure cooker spills into the wider village. Friends and enemies alike take stock: Cain’s erratic behaviour affects decisions at the pub, conversations in the square and even the fragile alliances the Dingles depend on. Belle and Sam’s grief is redirected not just at the world that took their loved ones but at the brother whose presence they need and whose absence stings. They talk of Cain’s fitness to lead the family — an indictment that lands hard. Sam pleads patience; Belle answers with bewilderment and resolve. The siblings vow to care for Kane whether Cain cooperates or not. That resolution is tenderness wrapped in steel.

This particular arc doesn’t rely on explosive, blockbuster moments — its power is steadier, slower, more devastating. The writers focus on domestic ruptures: missed tomb visits, a conversation soaked in booze at the garage, the texture of a family strained by loss. Each small scene is a tack hammered into place, constructing an atmosphere of inevitability. Cain’s confession, his outbursts, the smashed award — these are not isolated instances but threads that together form a portrait of a man pushed to the brink.

There’s also the echo of what might have been. Cain’s regret — “I should have finished him off when I had the chance” — is not framed as bravado but as a wound: he blames himself for failing to secure the justice Nate deserved, and that self-recrimination eats at his identity. He moves like a man half convinced he no longer belongs in the role others insist upon: protector, patriarch, the tough centre of a fractious clan. Instead, he’s brittle, reactive and often absent when he is most needed.